The Wizard condenses expertise from leading philanthropic, legal, and wealth advisors into valuable insights for you.

In just seven questions, the Wizard matches your charitable, financial, and personal goals with the right charitable giving vehicles.

Only you will see your answers -- be as honest as you can.

Giving outright gifts is the most popular way to give. Gifts are immediate and straightforward, and you have total control over making the gift. If you gift appreciated securities, you avoid capital gains taxes and receive a deduction for the full market value of the gift.

Outright gifts are simple, but that doesn’t mean that you can’t be organized and strategic. Yes, giving vehicles tend to encourage a longer-term perspective, but outright gifts can be just as effective if you have a good plan.

It’s likely that a portion of your giving will be in response to requests from friends and family, schools, faith-based institutions and community organizations -- and that’s great! However, for the portion of your giving that is proactive, you will have more impact if you add a bit of strategy. Consider the following:

Spending some time reflecting on these four questions will help you align your giving with your core beliefs. The most important thing is to develop some focus for your giving even if it's a “back of envelope” plan.

These groups also recommend top rated nonprofits:

Instead of selecting individual nonprofits, you can give to grantmaking intermediaries. This is a great way to focus your giving and leverage their expertise on a given issue. Intermediaries focus on key issues or geographies, develop comprehensive strategies for effecting change, evaluate the most effective nonprofits in the space, provide funding to them and measure their impact. When you give to intermediaries, they pool your dollars with others and re-grant to the best nonprofits working on the issue. Some examples include:

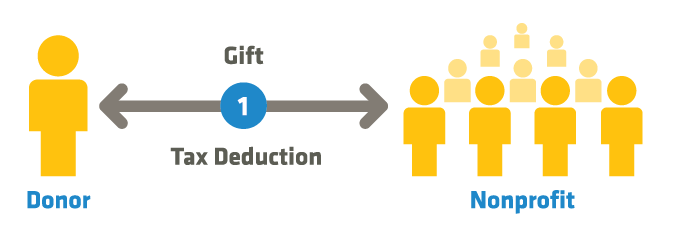

You make a direct donation of cash, appreciated securities or property. Then you get a tax deduction for the value of your gift. You can gift online, by mail, in person, or by wire transfer.

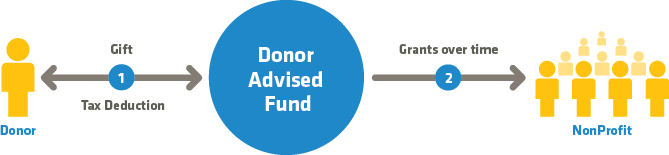

Donor Advised Funds (DAF) are the fastest growing and most popular charitable planning vehicle for good reason. They are a simple, low-cost way to make a donation now to a charitable account, receive an immediate tax deduction for the full value of the gift, and direct distributions to nonprofits over time. Essentially you are prefunding your future charitable giving in order to get tax advantages now. As a further benefit, these accounts grow tax-free. There were almost 2 million Donor Advised Funds in the US in 2022, with over $228 billion in total assets.

DAFs are provided by four primary types of sponsoring organizations – each with its own unique benefits and advantages

You create a charitable fund at the DAF provider, usually with a minimum of $5,000 - $25,000. You get a charitable deduction upfront at the time that you make the contribution to the fund, not at the time when the gifts are distributed to the nonprofits that you recommend. The fund administrator is responsible for managing the donations to grantees on your behalf. You make recommendations on how much, when and to which nonprofits the funds should be distributed, and the fund administrator executes the transaction, and provides due diligence, recordkeeping, grant letters and tax deduction documentation. The administrator charges a fee to cover the cost of these services that ranges between 50 to 150 basis points (0.50% - 1.50%) depending on the size of the donor advised fund.

Technically, donors can only recommend, or ‘advise’, which nonprofits will receive their funding and how much. The fund administrator has the final approval because they are legally and financially accountable for the expenditure and they must ensure that the contributions go to qualified charitable organizations. In practice, however, as long as the organization is a qualified 501c3 nonprofit and the grant is for charitable purposes, the approval is pro forma.

DAFs are sometimes referred to as a ‘light’ version of Private Foundations, since they offer similar benefits, but require significantly less time and money to set up and have far less administrative burden.

An ideal candidate for a Donor Advised Fund is someone who wants to make a charitable gift and get a tax deduction now, but wants the monies go to nonprofits over time. DAFs are perfect for those who want simplicity and flexibility.

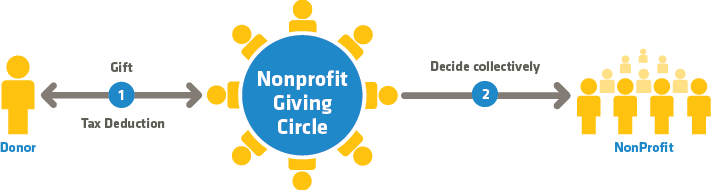

Giving circles are a popular way to join with other givers, pool your dollars, and decide collectively where to direct your combined resources. At thousands of giving circles around the country, people are learning about issues, evaluating the best approaches, and making grants to have the greatest impact. Donating through a giving circle is a great way to leverage your donations, gain philanthropy knowledge, and meet other engaged people. Participants often feel that their giving is more meaningful, because they have a richer understanding of the issues and have been actively involved in the decision-making process.

Like an investment club, a giving circle is a group of people who pool dollars and make grant decisions collectively. You can find giving circles through Philanthropy Together . Giving circles require an annual membership or partner gift. The amount varies widely, typically from $500 -$10,000 each year. The main reasons to join a giving circle are to participate, learn, and connect with other caring givers. If you don’t have time to get involved, then a giving circle probably isn’t the right vehicle for you. Giving circles vary in size and structure from informal groups to official 501(c)(3) organizations.

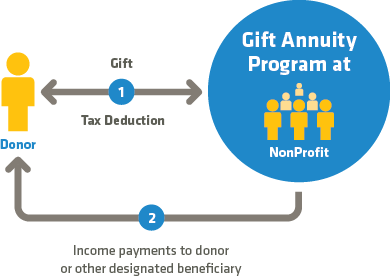

Gift Annuities are offered by most large nonprofits, universities and community foundations. You make a gift, receive guaranteed fixed payments for life and get an immediate tax deduction on a portion of your gift, all while supporting an organization that you care about.

It’s a simple contractual agreement that can be set up in minutes. You agree to make an irrevocable gift to a nonprofit and the nonprofit agrees to pay you (or another beneficiary) a guaranteed fixed income each year for the rest of your life. Upon your death, the remaining balance goes to the nonprofit.

The American Council on Gift Annuities publishes a suggested rate schedule based on latest actuarial data, expected rates of return on investments and the IRS 7520 rates (the rate that the IRS uses to value charitable interests). Since most nonprofits use this scheduled of rates, there typically isn’t a lot of variation in rates across nonprofits. The suggested rates for each age group are calculated such that the targeted amount to be realized by the nonprofit is ~50% of the original contribution. The tax deduction is calculated by subtracting the expected value of the payments from the value of the gift. Source: American Council on Gift Annuities

Also a part of the income you receive is tax-free because it is a return of principal. If you give highly appreciated assets, you will have to recognize some of the capital gain, but there is a financial benefit of deferring tax payments over time.

Most organizations have minimum age for donor to receive immediate payments, with most being about 60 years old. As a result, some nonprofits offer deferred gift annuities, where the donor specifies a date in the future when the payments begin. Deferred gift annuities represent about 20% of all gift annuities, though that percentage has been steadily increasing.

An older person who wants a guaranteed income for life, income tax savings now and has a favorite charity that they’d like to support long term.

Another likely candidate is an individual who has a favorite charity and is in their high earning years or who has had a large income/taxable event this year. They would benefit from setting up a Deferred Gift Annuity to get income tax savings now when they can really use it and an additional source of revenue in later years.

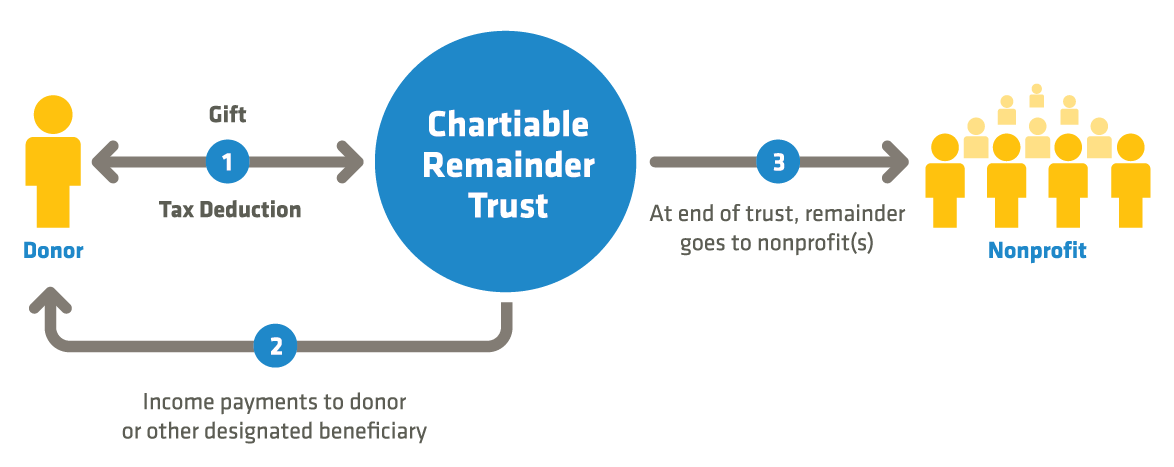

A Charitable remainder trust (CRT) is a common vehicle that enables you (or someone you designate) to: receive an income stream; get a tax deduction; and, upon death or at the end of a fixed term, give the remainder to charity. There are two kinds of CRTs: the charitable remainder annuity trust (CRAT) in which you receive fixed income payments and the charitable remainder unitrust (CRUT) in which you receive fixed rate of return on the trust’s assets. Therefore, with a CRUT your income payments will increase with gains in investment value and decrease with loses.

The trust is a separate legal entity that is set up by an attorney and managed by a trustee that you select, typically a wealth advisor, financial services company, yourself, or the charity designated to receive the remainderment (e.g. university, community foundation or larger nonprofit). If you choose the charitable remainder beneficiary to be the trustee, it will be easier to setup, but you will not be able to change the charitable beneficiary.

When setting up a CRT, you need to decide the following things:

After an attorney sets up the CRT, you’ll get a tax I.D. for the trust. Then you can establish a financial account for the trust into which the assets are transferred. The trustee has control over how the assets are invested, and is responsible for making the income payments and preparing the annual tax returns for the trust.

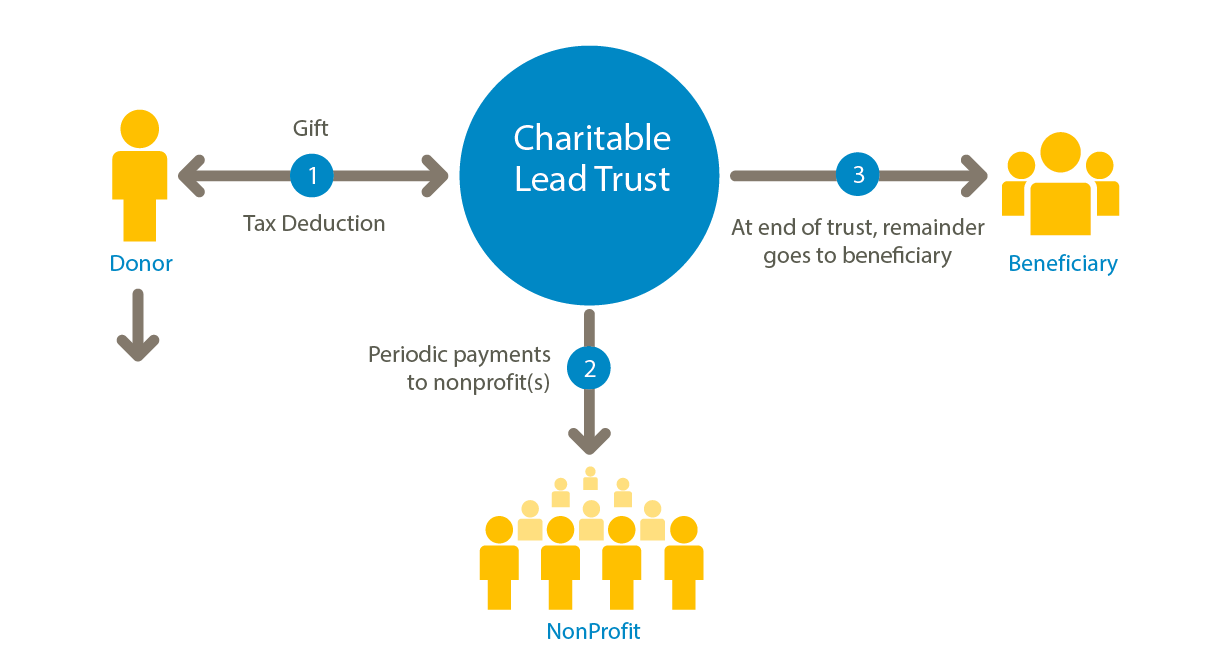

A Charitable lead trust (CLT) is one of the few charitable vehicles that lets you to transfer wealth to children (or others) in a tax-efficient way while you support your favorite charities. You contribute assets to the CLT; the trust then makes income payments to the charity(s) of your choice for a specific term or life. At the termination of the trust, any remaining assets are distributed to you, your children, or other named individuals. In some situations, you may claim an income tax deduction for the value of your gift, depending on the type of charitable lead trust that you establish.

While CLTs are much talked about, they are one of the least used vehicles with fewer than 8,000 in existence, in contrast to over 100,000 charitable remainder trusts and almost 2 million donor advised funds.

There are several ways to structure CLTs, each with very different tax implications. While this flexibility enables the donor to align personal and financial goals with their philanthropic planning objectives, it also adds complexity and makes it challenging to understand all the options and tradeoffs in order to choose the best structure for your specific situation.

The CLT is a separate legal entity that is set up by an estate planning attorney and managed by the designated trustee. Depending on the type of CLT, the trustee can be a wealth advisor, financial institution, yourself, or the charity receiving the income payments (e.g. community foundation, university, or other large nonprofit). Typically, the charities will only agree to be the trustee if you name them as the irrevocable income beneficiary.

You will need an attorney to set up the trust which will spell out the following features:

In grantor CLTs, the grantor (i.e. the donor) retains certain powers over the trust administration and keeps control over the assets inside the trust. As such, the donor is treated as the owner from the IRS’ perspective. This allows the donor to receive an income tax deduction, but he/she must also include the income from the trust assets on their personal income tax return each year.

In nongrantor CLTs, the grantor (donor) has given up sufficient rights and interest in the trust, and is not treated as the owner. As a result, the donor does not receive a charitable income tax deduction and likewise is not taxed on income generated by the trust. The trust is responsible for the income taxes generated and the trust can claim a charitable deduction each year for the income paid to charity(s). The trust is a separate entity, with its own tax identification number and files its own tax returns.

In a reversionary CLT, the remainder interest reverts back to the donor. In a nonreversionary CLT, the remainder goes to a designated beneficiary(s) other than the donor.

With an annuity trust (CLAT), the charity(s) receives a fixed dollar amount each year. With a unitrust (CLUT), the charity(s) receive a fixed percentage of the trust. Therefore with a CLUT, the charitable payments will increase with gains in investment value and decrease with losses. The CLAT is more popular because the annual payment is a fixed amount, and doesn’t need to be re-calculated each year as the trust changes in value.

The zero-out characteristic means that the IRS believes that there will be no assets left in the trust at its end, and hence there is no gift tax liability. If the trust is not 'zeroed out,' then a gift tax is assessed for the expected value of the assets remaining in the trust at the time of termination.

Each month, the IRS calculates an interest rate that is used to value charitable trusts. This rate, known as The IRS Section 7520 interest rate, is the percentage by which the government expects money will grow over time. In August 2022, this rate was 3.8%.

If the assets contributed to the trust are greater than the expected value of all the income payments to the charity, then the excess is considered a taxable gift to the beneficiary. You can structure a CLT so that the gift tax is zero by having the calculated present value of income payments to charity equal the assets contributed to the trust. The IRS considers this “zeroed out,” and no gift or estate tax is assessed. CLTs are most popular when the IRS interest rate is low, since there’s a higher likelihood that the trust assets will outperform the IRS assumed rate of growth, and thereby allowing the donor to transfer wealth to his or her heirs tax-free.

For example, back in March 2013 the IRS 7520 rate was 1.4%. If you set up a CLT with $1 million with a 20-year term and agreed to pay out $57,500 each year to charity, the IRS predicted the assets of the trust would be $0 at the end of the trust term, based on the expected earnings and charitable payouts. Hence no gift tax would have been assessed at the creation of that CLT. If the trust assets grew in excess of the 1.4% IRS rate, then the remaining assets would be transferred to the beneficiary(s) tax-free. For example, if the trust grew at 6% annually, then the trust would have over a million dollars in it at the end of the 20 years, which would be transferred tax-free to the beneficiary(s).

The donor then transfers assets into the trust. The trustee will be responsible for overseeing how the assets are invested, making payments to the designated charities, and filing annual tax returns for the trust as needed. At the completion of the trust, all assets left over are transferred to the named beneficiaries.

Each month, the IRS calculates an interest rate that they use to value charitable trusts. This rate, known as The IRS Section 7520 interest rate, is the percentage by which the government expects the trust’s assets will grow over time. In August 2022, this rate was 3.8%. If the assets in the trust grow more than the IRS Section 7520 rate, then there will be assets remaining in the trust at the end of the period. This remainderment will be distribution to the named beneficiaries tax-free.

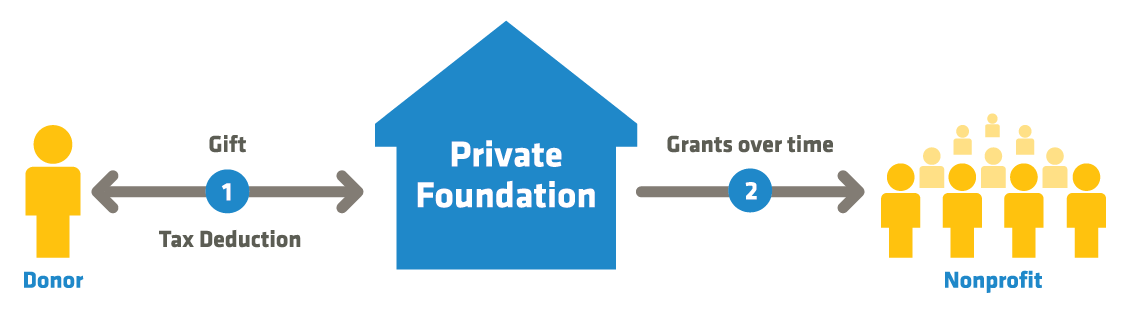

Private foundations are the cornerstone of U.S. institutional philanthropy. Private foundations were first established by industrialists such as Rockefeller and Carnegie in the early 1900s. Today there are approximately 145,000 private foundations with a over $1 trillion in assets. The Bill and Melinda Gates Foundation is the biggest at about $75 billion, but 98% of private foundations have under $50 million in assets. Private foundations are usually established with an initial large gift by an individual or family.

Historically, private foundations were established to operate in perpetuity drawing on the income from endowed investments to operate. But because of the flexibility that private foundations offer, they have become attractive to younger active entrepreneurial grantmakers. The “giving while living" movement and the Giving Pledge encourage people to actively donate during their lifetimes. From these efforts and others, philanthropists have embraced new approaches to solving problems and then found the right vehicle to serve their purposes.

Private foundations occupy a unique space: they are free to pursue any issue they desire, and take any approach as long as it is in compliance with charitable law. Some of the flexibility that private foundations offer include:

Tax treatment: While you can avoid capital gains taxes on appreciated securities and receive a tax deduction for your gift, there are lower limits on the allowable amounts for tax deductions. The maximum deduction is only 30% of Adjusted Gross income (AGI) if you donate cash, and 20% for gifts of stock or real estate. This compares to 50% of AGI for cash gifts, and 30% for stock and real estate for gifts to public charities. Furthermore, if real estate is given to the private foundation, the tax deduction is the cost basis, not the fair market value, of the property. When real estate is gifted to a public charity, the tax deduction is the fair market value. In addition to less favorable treatments for tax deductions, private foundation must pay an excise tax of 1- 2% on net investment income.

Regulatory and reporting requirements: There are more regulations governing private foundations in order to prevent personal benefit such as self-dealing. It is mandated that private foundations “pay out” 5% of the market value of assets annually for charitable purposes. Private foundations need to file a 990PF tax return annually, document expenditure responsibility for any contributions to foreign organizations, other private foundations, and any non-tax-exempt businesses. These compliance and reporting requirements generate significant ongoing legal, accounting and general administrative expenses, and time burdens.

A private foundation is created as a separate nonprofit, tax-exempt entity by an estate planning attorney. It is managed by a board of trustees, often consisting of family members. The donor then transfers assets into the foundation and receives a tax deduction. The trustees are responsible for overseeing how the assets are invested, making grants to charities, and complying with all tax and reporting requirements. Although you can establish a private foundation at any size, many recommend at least $5 million to start, given the significant startup and ongoing maintenance expenses. If you want to fund your private foundation initially with fewer dollars or reduce set-up time, consider using an online provider of support services. Foundation Source is the largest provider with 2,000 client foundations.

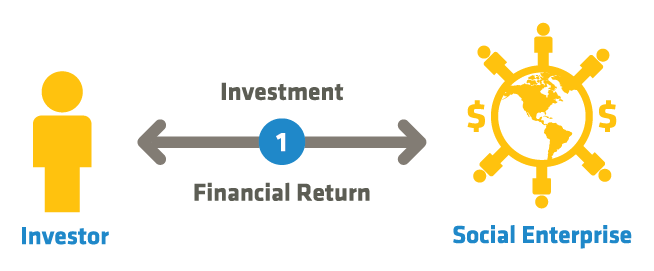

While not a true philanthropic vehicle, impact investing is an alternative approach that aligns donors’ values with their money. Impact investing is investing in social enterprises with the purpose of achieving a financial return while making a positive social and environmental impact – often referred to as a “triple bottom line.” The social enterprise can be a for-profit company or a nonprofit organization. The security can be private equity, debt, loan guarantees, or working lines of credit. The stage of investing can span from early/seed stage to later stage investments. Finally, the investment itself can be made directly to the individual enterprise, to an impact investing fund, or through a financial intermediary that offers impact investment vehicles.

Although it’s not charitable giving per se, impact investing is a paradigm shift for the field since it combines the financial performance goals of traditional business with social and environmental goals pursued by philanthropy. It is one of the hottest new trends and The Global Impact Investing Network (GIIN) estimates that the market was valued at $1.16 trillion in 2022.

An individual interested in impact investing can either invest with an impact investment fund or invest directly in a social enterprise. There are now many financial firms that have created impact investment funds focused on private equity, debt or a combination of both. For example, Calvert Impact offers numerous equity, bond, and alternative investment funds to meet the objectives and risk profiles of a diverse spectrum of investors. See ImpactAccess50 for lists of specialized impact funds managers. In addition, several mainstream financial institutions like MorganStanley and Goldman Sachs broker managed funds or offer their own impact investment funds as a new asset class to their clients. These funds differ by industry sector, mix of debt and equity, geographic focus, risk profile (e.g. stage of development) and financial performance. These managed funds typically have high minimum investment levels that make them only available to high net worth and institutional investors.

For investors who want to invest directly in social enterprises and entrepreneurs, there are networking organizations and incubators/accelerators that aggregate and vet social enterprises and help the best ones pitch their businesses to impact investors – both institutional investors as well as individual investors. They are the Y Combinators for social entrepreneurs and impact investors.

Finally, crowdsourcing platforms are emerging that enable smaller investors to fund startups and entrepreneurs. While most of the startups on these platforms do not have a social mission, investors can browse the listings to find social enterprises to fund. Some of the new platforms focus on geographic areas, asset class or a specific sector. Some popular crowdfunding platforms include:

Please choose

at least one answer.